Article • 10 min read

Why 2020 is the year for flexible workplaces

Por Susan Lahey

Última atualização em September 21, 2021

The 40-hour workweek passed into law in 1940. Back then, men went to work, and more than 70 percent of women stayed home. They might put in 12 hours a day of childcare, laundry, cooking, etc., but they didn’t get paid, so they had no income, and therefore they couldn’t even open their own bank accounts without their husband’s signature. The Civil Rights Act of 1964—designed to ensure people of all races, religions, and ethnicities were treated fairly in the hiring process—was still decades away. There was no internet, personal computer, or smartphone.

Fast forward eighty years and we’re in a very different world. Many couples share responsibility for income, home, and family. Technology allows people of all genders, races, and physical abilities to work, and even collaborate, from anywhere in the world. Research and experience has debunked the notion that the 9-to-5, 40-hour-a-week work schedule is the most productive. Yet, many companies still operate by that old paradigm, and struggle with how to create and manage a new workplace for a modern world. One of the most important factors for the way we live now is flexibility.

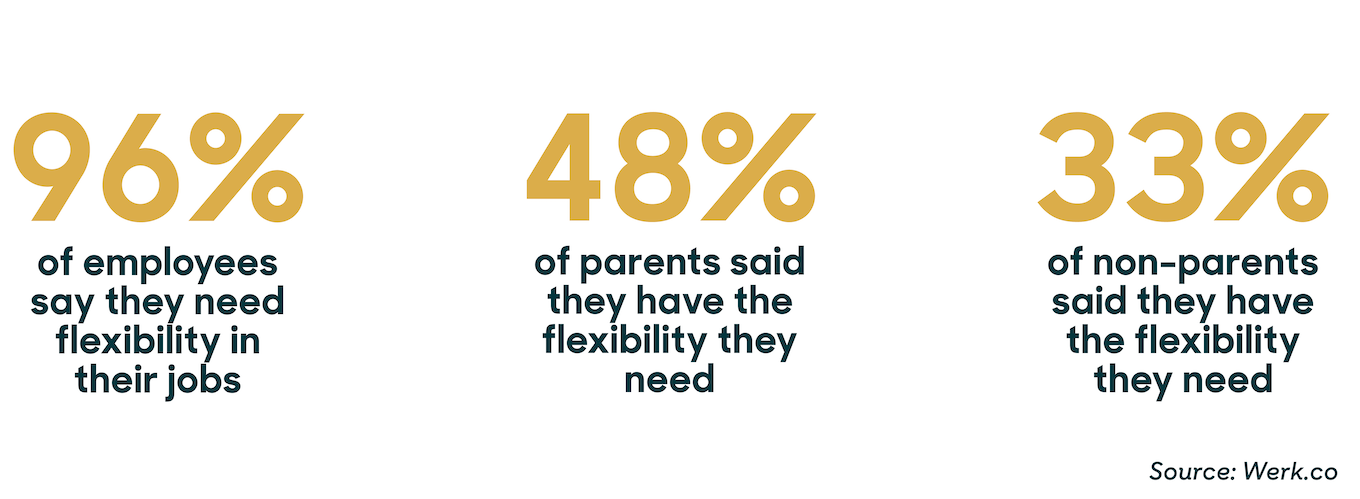

A study done by Werk.co, a platform for identifying opportunities for increased flexibility in the workplace, showed that while 96 percent of employees say they need flexibility in their jobs, only 51 percent of men and 34 percent of women say they have the flexibility they require in their current roles. The study further broke groups down between Millennials, half of whom said they have the flexibility they need, and GenX, of whom only 36 percent said they have the flexibility they need. Finally, 48 percent of parents and 33 percent of non-parents said they have the flexibility they need. Respondents included 1,583 white-collar professionals determined to be “representative of the U.S. workforce at large.”

Why flex the flexibility muscle?

Employees need flexibility for different reasons. They might need to take care of kids, parents, or pets; to address health issues; to increase productivity by working from home rather than commuting long distances to work. The variety of scenarios makes it tricky for employers to craft policies that are sufficiently broad and inclusive, but also ensure that the employees meet their responsibility to the company.

“There’s this idea among management of ‘if I let one person do that, it will open the floodgates and everyone will want to do it and how can I keep track of people working?’” said Ian Reynolds, an employee engagement and work/life balance expert who previously worked as director for Work/Life and Community Programs for Johns Hopkins University and currently serves as executive director for Higher Education Recruitment Consortium. Reynolds said employers tend to over-rely on the assumption that they can correlate productivity with being able to see people at their desks or workstations. They also fear that loosening up the hours or location requirements invites mayhem.

But, Reynolds said, creating more flexibility is unlikely to cause a rush for the door. “A lot of employees want a routine. They want consistency. A lot of people like going to the office and get rejuvenated by being around their colleagues,” he said. They just need “little tweaks” to make life and work work better together.

[Related read: Working moms need a new F-word: flexibility]

Helping identify those key “tweaks” is Werk’s job. Organizations rely on consistent systems and Werk’s research defined clear paradigms for creating flexibility. For example, the study defined a flexible job as a “full-time W2 role with a structured set of time or location-based modifications that ensure high compatibility between the needs of an employee and the employee.”

And it listed six specific types of flexibility:

Time Shift: The ability to adjust your working hours to fit your life

MicroAgility: The ability to step away for work for 1-3 hours to address an unexpected issue

Desk Plus: The ability to work away from the office at times

- Remote Location Independence: The ability to work away from the office most of the time

Part Time: The ability or option to scale back hours to part-time

TravelLite: The ability to take on only reduced travel

What researchers found was the most important types of flexibility are Desk Plus, MicroAgility, Remote Work, and Time Shift because these cover the bulk of the issues that arise for many different employees.

Syncing with life works well for women

Reynolds notes that many people who have kids, parents, pets, or others who are dependent on their care don’t necessarily think of themselves as caregivers. But the fact that they are responsible for someone else’s well-being makes it especially difficult to be unavailable for eight-plus hours a day. Women have traditionally held this role and kept the reality or struggle that they were juggling priorities a secret for fear of risking their careers. In fact, in Werk’s study, men were more likely than women “to believe that flexibility is offered consistently to all employees across their organization.” The reason, researchers said, is that men are probably less reluctant than women to ask for flexibility for fear it will keep them from being promoted or given big projects.

But an organization that fails to distance itself from this anachronistic way of thinking puts itself at risk. Women-led companies tend to perform better by every metric. Hiring and promoting women is much harder when a company doesn’t offer flexibility. The Werk report said, “Of the 30% of credentialed women who leave the workforce, 70% say they would have stayed if they had access to flexibility.” So flexibility powerfully impacts a company’s ability to reach diversity goals.

[Related read: The power of women-built brand experiences]

Flexibility aids diversity

Hiring women isn’t the only area where diversity is achieved through flexibility. Roughly 30 percent of respondents said they needed more flexibility to take care of health issues, including 30 percent who require flexibility to manage or accommodate for a disability or chronic illness. Some chronic conditions have flare up periods that leave people with enough energy during the day to do their work, but not necessarily to dress, commute, and manage life in a hectic office where they can’t stop and rest. Or they might require a medical device that’s awkward to bring in. So Desk Plus would solve that. Or, as the Werk study noted, someone who uses a wheelchair and uses mass transit might need to use Time Shift to travel to and from work when there’s less congestion.

Reynolds himself became a work/life expert after he and his wife had a child with Down Syndrome. He had been working with a program to identify and support gifted kids at Johns Hopkins. As part of that, he and his boss had taken a class on the importance of flexible arrangements. A few years later, the birth of his son brought “a dramatic personal shift, and part of the support I received when we found out about my son’s genetic condition was flexible scheduling—working from home, taking time off for his speech and occupational therapy.”

Because his world and priorities had changed so profoundly, Reynolds wanted to move his career in the direction of work/life balance.

For some people, the need for more flexibility for healthcare is less dramatic. They want time to work out, go to medical or therapy appointments, or to get a good night’s sleep. Again, it behooves an organization to accommodate that. Healthy workers tend to be more productive and almost 90 percent of workers whose companies have well-being initiatives would recommend their company to others.

[Related read: Be an #A11Y—why inclusive design is good design]

Productivity can soar

A workplace has distractions, primarily in the form of people: colleagues pop in with questions or pull you aside on on your way to the coffee station, or in the bathroom, or while you’re eating lunch. There are also those who bring donuts and pull everyone from their tasks to celebrate a co-worker’s birthday. It’s great—unless you’re trying to concentrate on a difficult problem or creative project and need to focus.

Similarly, commuting to an office takes time. Making sure you’re appropriately dressed, buying lunch out, commuting back home… all of this takes time that you could be focusing on a project you’re working on. Also, some people are just introverts. They need a lot of time alone. Too much social interaction, like 40 hours a week, drains them and reduces their productivity. For some temperaments and some projects, Desk Plus or Remote Location Independence are far better solutions to deliver results to the employer than requiring everyone to be at their desks.

In the past, employees’ “humanness” wasn’t really invited to the workplace. Personal issues were considered inappropriate to raise within the context of the workplace. Reynolds said he drew a picture of an employee with a giant switch on his chest that said Life at the top and Work at the bottom. The switch was in the Life position and the cartoon character was apologizing to his boss, saying, “I’m sorry, I forgot to turn off my life.”

That old system of expecting people to turn off their lives doesn’t fly anymore. But how can companies create systems that don’t inspire chaos and also accommodate all these humans and their varied lives? It begins with leadership. The Werk report noted that leaders are at something of a disadvantage in understanding how to solve this problem because people in higher levels of authority also have considerably more flexibility, which creates a disconnect between senior management and those they manage. If management doesn’t recognize the inflexibility that employees contend with, they’re less likely to address it as a structural or systemic issue.

Some jobs, of course, require that someone be in attendance for a certain period of the day: nurses, for example. But what about jobs where being present may be optimal for collaboration but not for individual employees? Leaders have to work with employees to determine the metrics that are truly important for job performance—beyond sitting in a desk 40 hours a week.

[Related read: How to keep remote employees from feeling out of sight, out of mind]

In a Harvard Business Review article on the benefits of the six-hour workday, organizational psychologist Adam Grant, author of Originals: How Non-Conformists Move the World is quoted: “The more complex and creative jobs are, the less it makes sense to pay attention to hours at all.”

So, what should be measured? Output? In a task that is creative or research-based in nature, the output might be only the tail end of a lot of hard work.

Contribution? The algorithm to really understand one individual’s contribution to an organization would have to be very complex.

What is clear is that the answer is not, like the 40-hour work week, one-size-fits-all. Companies need to set goals with employee input for what the workplace of the future. What constitutes high performance? What constitutes “reasonable accommodation”? How does everyone work best and still manage their lives? The Werk system is a good start, but the quest for a new paradigm is on its way.