Article • 11 min read

As technology advances, we question what it means to be human

Por Susan Lahey

Última atualização em July 14, 2022

Underneath questions about whether artificial intelligence can create works of art, or whether—and how—robots can take on human work, are questions about what it means to be human, and how our relationships to each other are changing as we build new technology and experiences. This came across loud and clear at SXSW 2019, from sessions about learning empathy through virtual and augmented reality, or when author Neil Gaiman examined the relationship between art and collaboration, or when Rep. Alexandra Ocasio-Cortez spoke out on disenfranchisement, or when journalist Michael Pollan talked about the ways that psychedelics can permanently shift a person’s fundamental understanding of life. The interplay of humanity in our digital and physical spaces reveals itself in some strange and creative new ways.

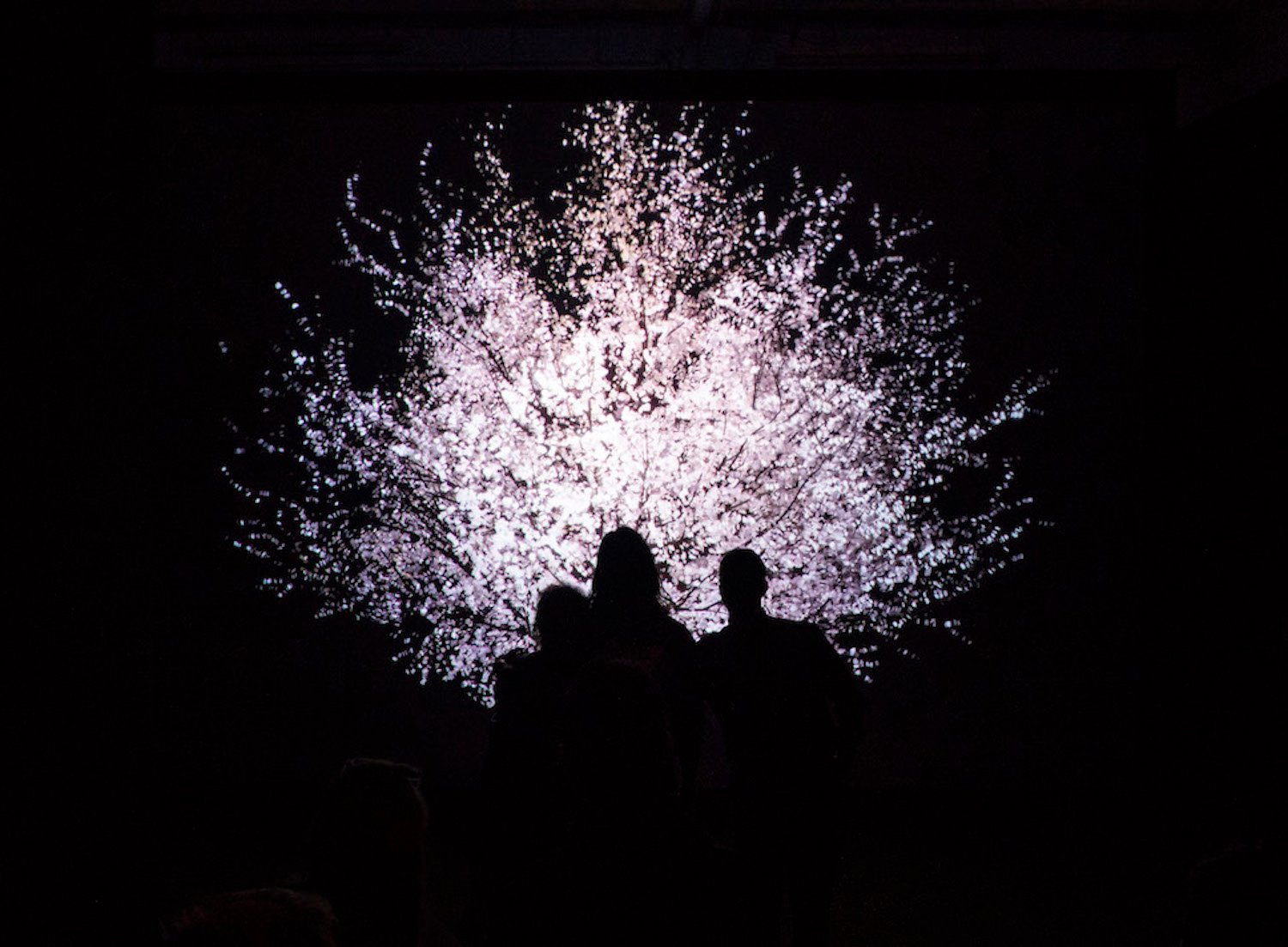

Case in point: In a dark room, strangers stood in front of a bare digital tree, on a screen in the dark, and held hands, causing the tree to light up and bloom. This was an installation by artist Lisa Park, who created Blooming after she moved away from her family and realized that Skype and phone calls couldn’t replace her need for physical touch.

Photo and video courtesy of the artist Lisa Park.

On the one hand technology is replacing human connection, on the other it reminds us we need it. And the awe-factor we feel when we see a cool technology-enabled experience can often remind us of a feeling similar to when we feel a hand clamped down on our shoulder or when we wrap a friend in a hug.

[Read also: Regulating AI—a call for transparency and ethical use]

We examine our humanity whenever we uncover something new about the mysterious nature of the universe, when old institutions fade or new technology is introduced. These days, things change so much, so fast, and the question of what it means to be human seems more pressing and more ambiguous than ever. We want it to mean more than being a class of bipeds. We want to believe that what we produce, how we think and relate, is more meaningful than what machines can do. As machines get better, that arena seems threatened, but if one thing was evident, we’re still humans building and leveraging machines for human use, solving problems we’ve arguably made for ourselves.

Emotional machines

Pamela Pavliscak of Change Sciences didn’t intend to study emotion. She’d started by studying technologies to discover what makes something easy to use, or boosts productivity, or increases efficiency, she explained in her “Emotionally Intelligent Design” session. “But every project I worked on, there it was, lurking below the surface, this emotional relationship we have with technology.”

On the one hand technology is replacing human connection, on the other it reminds us we need it.

She began to study technologies that incorporate emotion. There’s technology to detect emotion in drivers—useful since road rage and tiredness are the leading causes of accidents after drinking and texting. This tech is supposed to help the stressed driver calm down. The game Nevermind employs biofeedback sensors and increases in scariness as the player’s stress rises, designed to teach people to manage their emotions. Crystal is a plug-in that analyzes emails to detect and respond to the personality type of the email recipient. And conversational IVRs and chatbots are designed to pick up specific tones and words to identify an upset customer before a problem escalates.

But, according to Pavliscak, none of this artificial intelligence (AI) is being trained with sufficient complexity to deal with the reality of the human emotion spectrum. Microsoft Oxford’s facial detection software, among others, was trained using research on human facial expressions done decades ago by psychologist Paul Eckman. After the Paris bombings of 2015, the software read the facial expression of pictures of then President Francois Hollande as impassive. Probably, Pavliscak said, that’s not what he was feeling. It read the face of the person next to him, talking to a reporter, who had lost a couple of friends in the bombings, as “happy.” But, as Pavliscak said “a smile can mean a lot of things: it can mean uncertainty….”

Many AI programs are trained based on a view of the world that focused on increasing happiness or delighting customers. But that reduces the palette of human emotions, leaving out feelings of safety, contentedness, or inspiration to rise to a challenge, among others.

AI is like a toddler, Pavliscak said. It can see happy and mad, but it can’t cope with conflict or yearning. People are amazed, and a little freaked out, by how fast it can learn. But human beings process information every minute of every day (even in dreams) through all our senses, verbal and social cues, and via information-gathering. Machine learning is based on how we learn. Compared to us, AI is primitive. And yet, Gartner predicts that by 2022, our phones will know more about our emotions than our families.

For herself, Pavliscak is less concerned about the dangers of privacy and surveillance than she is with the dangers of technology messing with our emotions. For example, much technology now is designed to create engagement by poking at our emotions—from delight and entertainment to anger—in the short-term. We’re intentionally hooked into constantly hitting “refresh” to get that next shot of dopamine. That tweaks our emotions in a way that may not be healthy in the short- or long-term. And while these technologies can only handle that limited emotional palette, lacking the ability to respond to nuance, ambiguity and context, they have the seductive quality of being measurable, and we may very well overuse them.

Much technology now is designed to create engagement by poking at our emotions—from delight and entertainment to anger—in the short-term.

[Read also: Why smart, predictive CX experiences depend on hybrid workforces]

A proxy for vulnerability

Our humanity is also called to mind when examining the technologies that seem designed to help us avoid the painful parts of being human altogether—like being vulnerable with another human. Replika is a chatbot that uses a user’s answers to deep questions like—Do you consider yourself successful?—to ‘learn’ the user. Through texting back and forth, the user and Replika become “friends.” Some people say the kinds of conversations they have with the chatbot are much more vulnerable and intimate than those they have with other people.

Eugenia Kuyda initially created the chatbot with text messages and emails from a friend who had recently died so she could still talk to him. That was the inspiration, though Replika’s focus has since changed.

StoryFile, however, unabashedly lets people “speak to the dead.” In another of several sessions about AI and creativity—“AI and the Future of Storytelling”—StoryFile CEO Heather Smith explained how her company records video interviews with people so that when they die, their loved ones and descendants can have “natural” conversations with them. (When asked by an audience member whether that hindered the grieving process, Smith said, “I don’t know.”)

In many sessions, it was suggested that people felt safer being vulnerable with technology than with other people. And while technology can provide useful treatments for people with Autism or PTSD, it seems to be contributing at large to our sense of disconnectedness and loneliness.

[Read also: The psychology of rating: it’s hard, but better, to be honest]

Humanity and our connection to our work

In the U.S., people tend to identify heavily with their work. But at SXSW, most panelists talked about a “post-scarcity” future in which people no longer need to work because the robots have it covered.

One speaker to address this was Rep. Alexandra Ocasio-Cortez, who noted that technology has made it possible for everyone to work a lot less and produce a lot more. We could produce enough—in fact—for everyone in the world to have their needs met, even working fewer hours. Ideally, that means we can redefine our time—and identities—according to what we love. This sounds great, but it’s not happening yet.

At SXSW, most panelists talked about a “post-scarcity” future in which people no longer need to work because the robots have it covered.

In fact, many people are working twice as much as they did before. Sometimes this is to keep up with technology and sometimes to compete against it. We should be excited about the possibilities brought by technology, Ocasio-Cortez said; but we’re afraid of it because, in the U.S., “if you don’t have a job, you’re left to die.”

She reiterated that our relationship to our work defines our sense of self, and that those in low-paying jobs—many of which are at risk through advances in technology—feel the direct impact on their humanity and ability to grow and change. “We have been taught that we don’t matter,” Ocasio-Cortez said. “If you make less than $15 an hour you don’t matter. When you internalize that you don’t matter, you don’t do anything to change your lot because you don’t matter.”

Even artists, the one profession that seems uniquely human—existing to express the human experience and spirit—are now seeing competition from technology. Recently, a portrait created by AI sold for more than $400,000. The AI program analyzed 15,000 portraits and came up with one of its own—granted, minus a nose. But however accurately it can synthesize the work of other portrait painters, it has no sentience of its own by which to interpret another person’s essence through art. As Pavliscak said, there’s a lot of nuance, ambiguity, and context to being human. (Microsoft Oxford’s algorithm registered Mona Lisa as “neutral.”)

“People aren’t interested in push-button art,” said Douglas Eck, Sr. Staff Research Scientist at the Google Brain team in the storytelling session. “It’s much more interesting to watch people struggle and find something to say.”

Writer Neil Gaiman, speaking to a crowd of 2,400 in a ballroom in the Austin Convention Center, said something similar. When he and the late Terry Pratchett wrote the new Amazon Prime series Good Omens, “…it was me and Terry trying to talk about what it means to be human,” Gaiman said. And by his account, it took them years of painful—and delightful—back-and-forth communication, a process that arguably can’t be replicated by machinery, at least not in the same way.

Dissolving our identities to build something new

There’s another way we’re exploring our humanity, and it dovetails precisely with the future of technology. In the epicenter of change, Silicon Valley, some are experimenting with dissolving their identities as they know them, through use of psychedelic drugs.

Journalist Michael Pollan, author of How to Change Your Mind: What the New Science of Psychedelics Teaches Us about Consciousness, Dying, Addiction, Depression and Transcendence, drew a crowd that packed the same ballroom. Pollan’s book investigates the long history of scientific research into using psychedelics—like LSD and psilocybin from ‘magic’ mushrooms—starting in the 1940s. Scientists have successfully used the drugs to treat everything from alcoholism to depression. When used on terminal cancer patients, it often affected such a huge shift in their ideas about their own nature and the nature of life that they no longer feared death. Recently, the Food and Drug Administration again approved research with psilocybins to treat drug-resistant depression.

Scientists have successfully used the drugs to treat everything from alcoholism to depression. When used on terminal cancer patients, it often affected such a huge shift in their ideas about their own nature and the nature of life that they no longer feared death.

As Pollan said during his session with interviewer Tim Ferris, psychedelics seem to quiet a part of the brain that serves as the “traffic cop” of the mind that guards one’s identity. This allows different parts of the brain to communicate with one another. In the process, the rigid ideas one has about who they are can dissolve and a new, expansive understanding replaces it. In Silicon Valley, many tech creators are reported to microdose these substances in order to free their minds and release creativity. And many who take psychedelics people report the sense that the walls separating them from the rest of the universe disappear, giving them a sense of oneness, love, and immortality.

Several days of SXSW were like watching some of the world’s most brilliant minds hold up the idea of humanity to a light and turn it this way and that. If we think of our value as humans being tied to our work, and robots can do it, then are they human or is being human something else? If we think of our value as being emotion-based, which machines can learn to read, then they are again encroaching upon our humanity. And if our traditional concept of identity can be melted by a mushroom and replaced with something ineffable that lets us calmly face our own end, what does that say about who we have always thought ourselves to be? There weren’t a lot of answers at SXSW. But there were a lot of important questions.